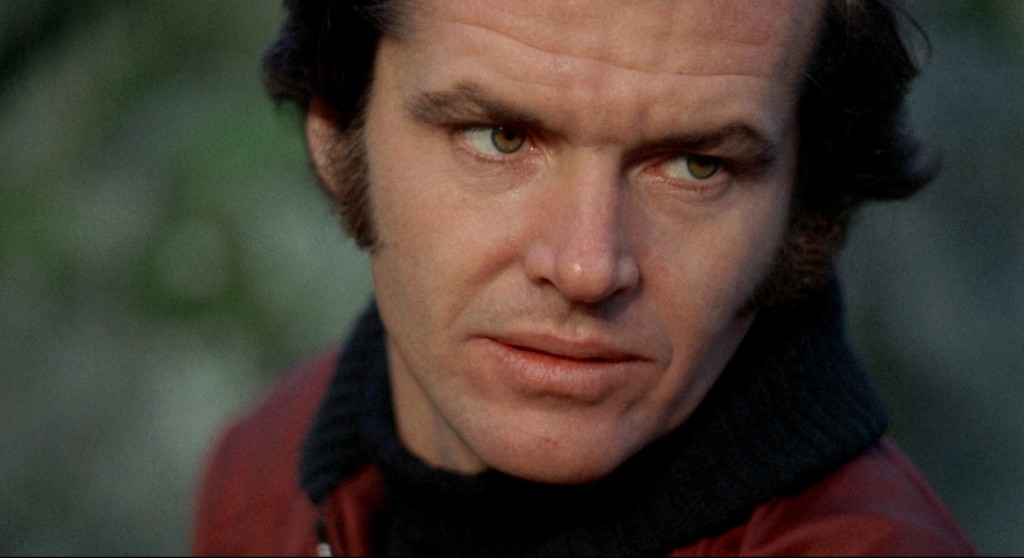

“I move around a lot, not because I’m looking for anything really, but because I’m getting away from things that get bad if I stay,” says Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson), the protagonist of Bob Rafelson’s 1970 classic Five Easy Pieces. Bobby Dupea is The Guy who Never Grew Up, and this line of dialogue spoken during a revelatory speech to his incapacitated father, perhaps best sums up his character, as well as the overall mood of the film. Recently restored in a high-def digital transfer, and released by the Criterion Collection on Blu-ray with a slue of documentary-heavy special features, Five Easy Pieces maintains a relevance to our present time in its depiction of modern man’s struggle with his inclination toward self-destruction.

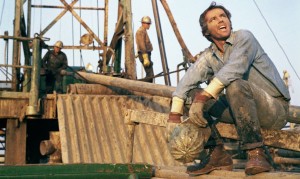

“We both know that I was never really that good at it anyway,” says Dupea in that same speech to his father. The “it” here is both his now-abandoned stint as a concert pianist, a stint that Dupea himself deemed a failure, as well as anything remotely resembling a mature and at least semi-functional adult life. Which he is not “really that good at,” at all. When we meet Bobby, he is a thirty-something working-class oil-rigger in California. He is a good-time guy who hits on anything that moves, while maintaining a reluctant relationship with sweet ‘n sexy (and just a wee bit obtuse) waitress Rayette (Karen Black). He is also, in Jack-Nicholson fashion, angsty and quick to lose his temper. As the picture rolls on, it becomes clear that Bobby has chosen to live a low-standards life because he has deemed himself incapable of living a high-standards one successfully. He is intent on punishing himself, because he seems to have misinterpreted the purposes of life’s components. To live well is to be the best version of oneself as often as possible, not to be the best version of the bestest out of everyone, period. This attitude of impossible perfectionism is rooted in the enemy of enemies: fear. And Bobby Dupea is one fearful man. He quits his oil rigging job and heads for Los Angeles to see his sister Partita (Lois Smith), another pianist working on a recording in a studio there. She informs Bobby that their father, who Bobby hasn’t seen in years, is dying. He heads home to Washington state to visit him.

“Can’t you understand it was the feeling I was affected by?” asks Catherine (Susan Anspach), a beautiful young pianist engaged to Bobby’s brother Carl (Ralph Waite). They are all at the Washington state house and Catherine has just heard Bobby play what he calls “the easiest piece” on the piano. She is laughed at by him for having had an emotional reaction to the experience; he played the Chopin piece better as a kid he feels, saying “I faked a little Chopin, you faked a big response.” Bobby carries around the Holden Caulfield notion that those in the adult world are all phonies; thus, he must avoid any pursuit that may involve phoniness. As for the “feeling” that Susan was affected by, Dupea insists that he “didn’t have any.” He is caught up in his own childish beliefs in perfection, judgmental about statistics, facts and figures. Rather than use these beliefs to motivate his own abilities and talents, Bobby uses them as an excuse to not have to try. Meanwhile, as Susan insinuates, feeling is as important a goal as advanced technique, in art and in life, because there will always be a better player somewhere. Instead of asking oneself “How perfect was the performance I just gave?” the artist should ask, “How did I feel during the performance I just gave? How much did I feel?” But Dupea does not view matters this way; he quickly turns Susan’s compliment into one with sexual innuendo, for he is comfortable dealing with his emotions that way, as teenagers are.

“You’re all full of shit,” Bobby shouts at the intellectual guests gathered at Carl’s cocktail party, after they ridicule Rayette. She has turned up unannounced after Bobby abandoned her at a local motel, too embarrassed to introduce her to his family. Conscious of his own holier-than-thou judgment of Rayette, Bobby blames others (“pompous celibates!”) for doing the same. We might applaud his speech at this particular moment, having had enough of the laborious cerebral chatter on screen as well. Bobby’s accusation though, is not limited to these snarked-out guests, but instead seems to speak for his opinion of the entire mature responsibility-ridden world of adults that he refuses to be a part of.

“I’m fine, I’m fine,” Bobby utters in the film’s last scene, when he again abandons a pregnant (with his child) Rayette at a highway rest stop, this time seemingly for good, hitching a ride with the nearest truck driver in another escape attempt. His life seems to have been a series of these, for he refuses to buy into anything or commit to anyone. The truck driver offers Bobby a jacket because he is shivering. “I’m fine, I’m fine,” he insists, though we know that he isn’t and that he won’t be. A real man would have broken up with Rayette to her face instead of running away. A real man would at least come to terms with his current situation, taking credit for everything, good and bad, that led him there. Bobby is determined to remain as anonymous as possible, even to himself, scared of risking notoriety, scared of being responsible for maintaining any sort of success. In an earlier scene back at the Washington home, Bobby makes another pass at Susan and she turns him down. In her eyes, he “…has no respect for himself, no love of himself, his work, his friends, his family or something… how can he expect love in return? Why should he ask for it?” Well said.

This 2015 Blu-ray release from Criterion puts forth an excellent package of a disc, plus a stellar essay by critic Kent Jones. Much of the provided bonus features include interviews with director Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson, during which the origin story of the culture-defining BBS Productions team, responsible for such era classics as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), is articulated in detail. The zeitgeist of the 1960s in America and the country’s transition into the 1970s, which ushered in the American New Wave of cinema, is discussed in depth and very satisfyingly at that. The best extra is the more specific piece Soul Searching in Five Easy Pieces (2009), in which Rafelson discusses the development of the film’s screenplay by Carole Eastman (credited as Adrien Joyce). Here, he explains how he had wanted the Bakersfield, California scenes to look drastically different from those filmed in Washington state. The neon signs of Bakersfield were intended to imitate the American town and city looks of Edward Hopper’s lonely paintings. A classic American film with classic American (and Oscar-nominated, for Nicholson and Black) performances, in a redone reworked rewonderfulized Blu-ray set.