“Days, where’d you go so fast?” Gerry Beckley asks in “Bell Tree,” his bittersweet beauty-soaked song on America’s Hearts album. The band’s fifth studio recording, which also featured Beckley’s chart-toppers “Sister Golden Hair” and “Daisy Jane,” was produced by George Martin and released in 1975.

Beckley’s latest solo record Carousel is due in stores next month (September 9th) via indie label Blue Élan Records. Over the course of the album’s nine original tracks and three cover songs, Beckley offers up more seasoned articulations of his “Bell Tree” question. The irresistibly-catchy “Tokyo,” the Beatles-ish “Lifeline,” and the poetic “Once a Distant Heart,” all deal directly with our mortal inability to transcend the weight and power of time passed, passing, and soon-to-be-passed.

Other artists who have come to the same philosophical conclusions that Beckley has on Carousel might have been tempted toward anger, regret, fear, or perhaps worst of all, to wear Cynicism’s Crown of Superiority. Consider what its tracks titled “Minutes Count” and “Serious” may imply.

But Beckley seems to have taken the other road, the one on which happiness and personal power reside. His McCartney-esque gift for melody still reigns supreme on Carousel and his lyrics showcase a healthy dose of realism and inventiveness, at one point even daring to utilize the logistical word “Zihuatanejo,” a move worthy of Warren Zevon himself. Beckley’s thoughtful renditions of Spirit’s “Nature’s Way,” Gerry Rafferty’s “To Each and Everyone,” and Gerry and the Pacemakers’ “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying,” jive well with the rest of Carousel’s thematic content and allow the listener to reconsider the familiar songs in a newly visioned light.

Along with Dewey Bunnell and Dan Peek, Beckley founded America—in England—in 1970. Their ’71 self-titled debut album (which would include the immense hit single “A Horse with No Name” on its ’72 re-release) introduced an acoustic-forward, compositionally-seductive, nature-and-love-themed aural universe that lasted for a string of commercially successful and artistically remarkable records. These records, many whose titles begin with the letter “H,” are as worthy-of-praise in 2016 for their overall production and top-notch songwriting as they were upon their initial release in the 1970s. Though Peek split in 1977 for a variety of reasons and sadly passed away in 2011, Beckley and Bunnell still tour and perform as America to sold-out crowds across the nation from which they stole their name, as well as the rest of the globe.

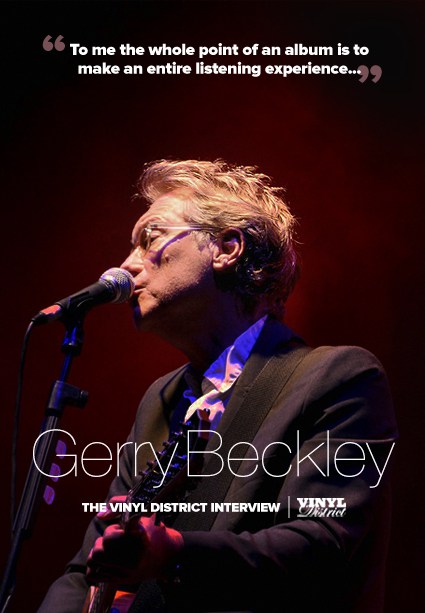

In conversation with Gerry Beckley, we learn more about the origins of Carousel, his and America’s compositional processes and musical influences, and the story behind suite song “Hat Trick,” the only America track penned by all three band members—Beckley, Bunnell, and Peek.

I want to congratulate you on your new album Carousel because I think it’s really incredible. What was the developmental process like for the record? How did you come up with its aesthetic?

I had a studio in my house—I moved a few years ago—but I had a studio in my house for decades. So, a lot of the time that I was home, I would record. I’m always writing; if I’m not actually putting it down on tape I’m making notes or using a voice memo machine for melody ideas. So there’s never a shortage of ideas, it’s really more a case of finding the time to put them down and work on them. Therefore this album covers quite a variety of years and material, some of it right up until very recently, and some of it from quite a long time ago.

Do you have a set compositional process that you employ? Or is it more just how it happens to happen?

First of all, some people just write music and others are lyricists and stuff. For Dewey and I, and many others, we happen to do both. So in that case my particular formula is almost non-existent; I’ve been starting to take musical ideas and head to a piano or guitar, with absolutely no lyrical content. Or sometimes it’s been the complete opposite—our dear friend Jimmy Webb, the composer, always trained us to keep a running list of titles. He would almost start with the concept of the title because he felt the title represented, and provided a snapshot of, what the entire piece would eventually become. So we do that, I do that, or I scribble up a lyrical idea and try to find music that fits it. Compositions can really come from completely opposite directions.

I heard, on this particular record and on a lot of America records, such a great mix of hardcore rock ‘n’ roll songs and singer-songwriter style songs. I think “Green Monkey” is one of the best rock ‘n’ roll songs I’ve ever heard. I don’t recall if that’s your song particularly…

It’s Dewey’s but thank you, and I’ll pass it on to him. We’ve added that back to the show recently.

Wow, I love it. But I also love your mellower material like “Till the Sun Comes Up Again” and “Daisy Jane”—just the best. I think that on Carousel there is the same balance. “Tokyo” is this catchy pop-rock track and “Carousel” is this introspective, quieter number. Do you do that on purpose? Do you make sure that you have a balanced mix?

Yes. Well, of course. I mean to me, we used to call an album forty minutes, with twenty minutes of each side on vinyl, and with CDs it became a bit longer. To me the whole point of an album is to make an entire listening experience, not for the listener to just go in and cherry-pick “Oh, I like track seven.” We grew up in the era of pivotal albums, like Pet Sounds, Rubber Soul, Sgt. Pepper’s. We had great training that way, in terms of—we had great targets to shoot for. In particular one of the challenges when you do a solo album I’d say would be that it’s just you singing all the songs. If it’s a given that you’re at least a voice on every song, then what are your other variables? There’s tempo, mood, etc. So if there were any overarching concepts or directions, that would be one of them. I would never, I don’t think, do a cluster of eight “Daisy Jane”-ish type songs. To me, they would water each other down.

I think thematically too, Carousel has a great unification of ideas. Theme-wise and creed-wise, the album seems to be an admirable refusal to be cynical. There is the temptation to become cynical as a person goes forward in life, because he’s done all this great stuff, yet is still exposed to the same annoying elements of life too, I would think. This comes up in relationships a lot I feel, and on this record it is addressed in “Minutes Count” and “Lifeline.” Beautiful songs, but there seems to be an underlying “time to get real” statement there.

Thank you—I guess thank you (Laughs). It wasn’t until I listened to the whole album—because you work on each song individually and it’s usually one of the latter steps when you consider them all together and start to consider track sequence. It wasn’t until I had the whole album on a disc and in my car, driving around, making sure that the song segueing worked, that I realized there was quite a bit about time there, thematically speaking. We’re always—at the risk of quoting general themes, like life and stuff. But this album seems to have quite a bit about time and the importance of time and how to handle it. I’ve always said time is not the enemy, it’s the challenge. Songs like “Carousel,” like how we’re basically on a spinning wheel here, and in “Minutes Count,” it’s there.

“Carousel” is a really great track, about the ride of life—you say it better than that, but—you’re older each time you pass around the carousel and you know it can’t last forever, but the same place markers are there, you’re on the same route, the same issues come up. Have you ever read the Ray Bradbury novel Something Wicked This Way Comes?

I haven’t—and I read a lot. I’m almost buried in stacks of books here in Venice (California), but I love to read and will add it to the list, thank you.

In the book, the carnival’s carousel is an eerily literal time machine, and depending upon whether the characters want to get older or younger, they can get on and ride a certain amount of rides around. It reminded me of your song.

Far out, I’m familiar with it for sure, but I will read it.

In your song “Serious” you mention living life in soft focus—I know you’re a photographer—but I liked how the idea suggested that too much self-evaluation can paralyze a person, so that the person remains stuck in the past, when he should be moving forward into the future. The problem is that moving into the future can be kind of scary.

Well, there’re both sides of that and I tell you, everybody’s mind—well a degree or two in one way or the other can really make a tremendous difference as you navigate your own challenges. Our dear friend George Martin the producer, may he rest in peace, as he aged had the most wonderful outlook. His hearing was going, his wife was having health battles, but as he went into his eighties he saw it as—what a gift to be able to experience life. I wish that I and everyone I know could be able to lock onto that particular concept. But it’s far easier to say. I have sons and I think, to have learned these life lessons, it would be great to impart them on my kids. But you have to earn them as well as learn them. With all the meditation books there are—if you don’t apply it to your life, it doesn’t work. I’ve never stopped loving what I love, I continually go back and remind myself.

I think that’s great. I think too “Nature’s Way” was such a lovely choice of cover songs for the album because it fit in with the theme. It reminded me of a toned-down Steely Dan-esque warning-against-decadence track, but in a more hippified way. Like actions against nature, against human nature, will catch up with us, which ties back to the time theme. I was wondering too if you considered yourself ecologically-minded? I’m using that phrase because I found this article in The Lakeland Ledger from ’75—in which the interviewer, calls you, America, “ecologically-minded” because you always had a lot of plants onstage, which I thought was really cool. But then she makes a point about how when you answer her question, you’re drinking “a non-alcoholic beverage.” Which I thought was hysterical—I mean she was trying to make a point about the band’s image…

(Laughs) Well, there won’t be any more of that, drinking non-alcoholic beverages. My partner Dewey has been outspoken from day one, as much as people would want to assign meaning to “A Horse with No Name,” plants and birds and rocks and things—the guy is an outdoorsman to the nth degree. Our joke is that he writes the outdoor songs and I write the indoor songs. But I had grown up in that pro-nature environment. Dewey lives out on a lake in Wisconsin and he’s really connected to nature, so he’s an inspiration in that regard.

Back to the covers—recently I’ve been into that Gerry Rafferty hit “Right Down the Line,” such a great track, and when I saw that you covered one of his other tracks “To Each and Everyone” on this record I was super-excited. How did you decide to cover that particular song?

I love his album from ’71, called Can I Have My Money Back? He was in the Humblebums with Billy Connolly, who eventually became a Scottish comic. I was a big fan of them, and then Gerry Rafferty put out a solo record. I love the whole album from start to finish but “To Each and Everyone” was my favorite. So I kept it as a personal favorite for all these years and my version on Carousel is similar, though I did add signature harmonies and stuff later in the song. I was a huge Rafferty fan from day one. I’m kind of surprised that I never met Gerry because I do tend to look up my heroes. When we first moved to LA I remember we went out to Hawthorne to meet Emmett Rhodes, because we were big fans of his albums. Our dear friend and engineer Geoff Emerick did some Stealers Wheel stuff. It’s a great album though, I highly recommend it to anyone who’s got a little spare time to look it up, not sure if it’s even available anymore. It was one of those great records like McCartney’s first album, very simple, which was part of its charm.

I did find the Rafferty album on Spotify, though how artists feel about Spotify, financially speaking…

Well, that would be another discussion. The technology and the access it provides are miraculous, but that would be a long discussion about revenues and the remaking of the entire industry.

What do you think this record, Carousel, says that your America records and previous solo records haven’t said yet?

There’s a slightly louder presentation on this record. I have a new label that’s helping me promote it; I’m doing a showcase in LA next month. Every record is a snapshot of its own time, but it doesn’t mean that all of its songs hover around that era too. This one was recorded over a wide period of time, but it gives me a slightly different focus. I do interviews more, which gives me a chance to think about the record and gives me others’ opinions about what they hear. I enjoy it, it’s great. Both Dewey and I are pretty busy with the schedule that we have; we perform about a hundred shows per year as America. These things to a certain extent have to fit in the gaps, but they’re good gaps. I’m happy with the work and I love this album.

Did you realize anything about yourself while making the record?

There’s some personal stuff in the album, you know…“Lifeline” was a personal story. The song “Widow’s Weeds” was a dream—I woke up in the middle of the night with the opening lines. The next day I went in and cut it to an Appalachian kind of sound, like an old scratchy record. So each one’s got a bit of a backstory to it—the process is fascinating.

In terms of your America work, I feel that the whole albums are so fantastic. Your singles were extremely successful and incredible in their own right, but do you ever feel like that the reputation of the singles overshadows the stellar album work?

Albums are a lot of work and you always do the best you can given the circumstances, like in making a movie. You might have a great director, cast, script, but for whatever reason—the editing or something—it doesn’t come together. We’ve done enough records to know that’s the way it can happen in recordings. There’s not a thing we would change, we had so much success with radio and singles and stuff. But the hits lead people to explore what albums they stemmed from. There’s no way to slice that which isn’t good news.

Can you talk a bit about America’s “Hat Trick”? It’s eight minutes long and there are so many different sections of it. Did the three of you write it together—Dan, Dewey, and you?

We put it together, from different bits. When we put it together we had already established a pattern. Each of us would contribute three songs, maybe four, to an album and then we’d pick one or two covers—we’d done it on Homecoming. With the song “Hat Trick” we thought hey, let’s just put together a medley of stuff. We each had a few parts that weren’t yet complete songs and rather than iron out each one of those into three-and-a-half-minute tracks, we combined them. That’s how it happened, and I’ve always been a fan of that track. I’ve been threatening to include it in a symphony show on occasion, I told Dewey. Hat Trick was a great album, we had a lot of fun making it—it was a lot of work though. It contributed to the change that led us to George Martin who became our producer for a time. It had become more and more work to produce the albums ourselves.

When you used string arrangements on your albums, did you write those parts yourself? Did you use sheet music?

Sometimes. Hat Trick was the first one with strings and we used Jim Ed Norman who had been working with The Eagles. He worked with them on Desperado. But I think that the three of us had pretty clear ideas on what we were looking for, what we wanted the strings to do. That changed with George Martin; his abilities were off the charts. So it was an honor to turn our material over to a guy of that caliber, if you think about what he contributed to “Eleanor Rigby” and those kinds of arrangements that were just so pivotal to what we now view as those songs. I’m sure Paul’s “Eleanor Rigby” was fantastic from the get-go, but the producer and the arranger took it to another level.

I’m sure that he loved working with you guys with the level of songwriting that you were showing up with.

We had a great time; I group the George Martin years as a single highlight though there were seven different projects, including the live album. But the live album was recorded during several nights at the Greek Theater with Elmer Bernstein conducting the LA Philharmonic. It was a fantastic experience.

Do you feel that the sound of America changed a lot when Dan (Peek) left?

You know, the strength of three people is a good thing; we could pack the vocals and songwriting into the work, rather than just going back and forth between two guys. But also at the time of Dan’s departure he was going through so much personally—we couldn’t continue to work or book any more dates. It was the best thing for Dewey and me, but it was also the best thing for Dan. It gave him the time and clarity to make some major adjustments in his life. He went through a religious conversion. So we all think of it as a positive experience, though there was a lot of sadness, in that the original formula had to be disbanded. But it gave Dewey and me a chance to carry on and successfully so.

Have you ever thought about working on a jazz record?

I love jazz. A few years back I was on a radio show that went into what songs people had on their iPods. Looking at mine, I realized that—while I had all the classic Beach Boys and Beatles albums—I had more albums by Miles Davis than I had of any other artist. So I thought that was interesting, and I think jazz appeals to me because—the mindset of a jazz player, and his ability, and the necessary chops to play jazz—what he can do with his heart, mind, and hands—is beyond-beyond. I think that’s why I’m drawn to it.