Fifty years into a legendary career, most bands are content to rest on their hits, releasing bland blues covers albums or bored-yet-pleasant regurgitations of their earliest work. Procol Harum is not “most bands.”

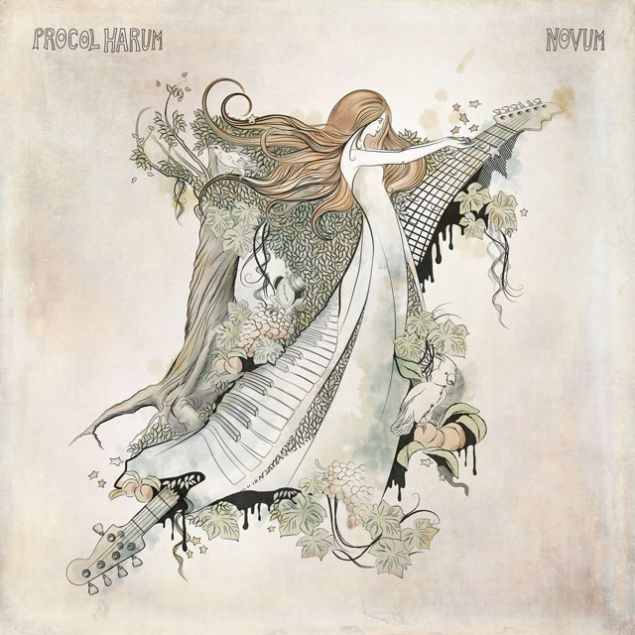

On the 50th anniversary of their debut album, the English prog rock icons continue to remain a singular force in modern rock music, embracing the new-song, best-song philosophy on their first album in 14 years, Novum, out on Friday, April 21, via Eagle Records.

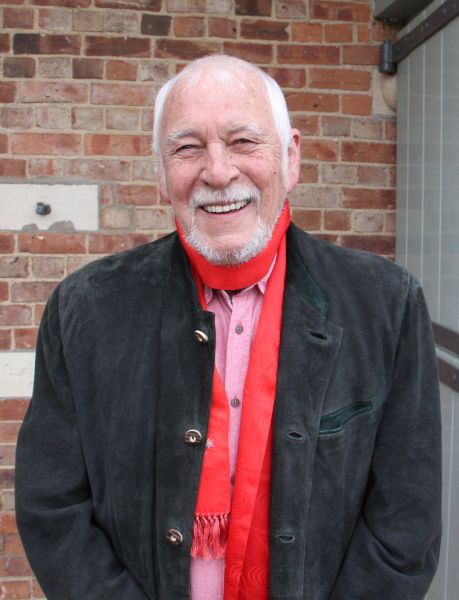

Singer and pianist Gary Brooker, largely responsible for the band’s best songs, is the only original band member present on Novum—the current lineup also includes Geoff Whitehorn (guitar), Matt Pegg (bass), Josh Phillips (hammond, montage), and Geoff Dunn (drums)—yet the distinctive sound the band established in the ’60s permeates much of Novum’s 21st-century aural space, making for an album of exquisite rock ‘n’ roll.

A testament to Brooker’s charisma, his blues-soaked Ray Charles vocals and soulful yet classically informed piano work still sound as vibrant as ever—every song maintains the trademark, instantly recognizable swagger we first fell in love with in 1967 on “A Whiter Shade of Pale.”

The single dominated British and American charts upon release, ultimately selling over 10 million copies. Of course, Procol Harum’s released a plethora of brilliant albums since then, too—the 1972 live album recorded with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, which topped the US Billboard chart and included the superb “Conquistador,” Grand Hotel (1973), and most recently 2003’s The Well’s on Fire.

For most of their career, Procol Harum employed the lyrical prowess of Keith Reid; for Novum, however, Brooker and Pete Brown (best known for his work with Cream) take over lyrical duties, managing to direct Procol Harum’s sometime lyrical obscurity toward a slightly more accessible territory. Still, the band’s trademarks of continental intrigue, European regalia, romantically moody ambiance, and an unwaveringly subtle sense of humor reign supreme.

Over the course of the record’s 11 songs, Procol Harum offer up earnest and varied responses to the rebirth plea they first made on “All This and More.” The jived-up, jazzed-up album opener “I Told on You,” the romantic and temporally-aware “Last Chance Motel,” and the spiritually-charged anthem d’freedom “Sunday Morning” all emphasize the power of an individual to insist upon his own truth.

We recently caught up with Brooker to discuss the origins of Novum, how he continues to keep his writing process fresh 50 years into his band’s career, and what it’s like to begin again, again.

Congratulations on Procol Harum’s new album Novum, it’s such a wondrous record. How did the decision to embark upon a new project come about? Was there a lot of planning ahead of time, or did it come together more organically? It’s been 14 years since the release of The Well’s on Fire.

I suppose organically, which is better. Over the past couple of years it’d been said that perhaps we should do some more, and we’d say, “yeah, we’ll get ‘round to it.” Last summer, somebody mentioned that this year, in 2017, Procol Harum would’ve been going for 50 years. I thought we couldn’t just let this drift by, couldn’t just have a party or something. And let’s put it this way: it being 50 years was good inspiration for us to write some new songs, get into the studios, and do them.

Could you have imagined this kind of longevity when you first started out? Could you have anticipated being a 50-year-old band?

Not at all. I was probably 20 when I started Procol Harum; nevertheless, I didn’t think it was going to last forever. I thought at the time, “this is good”; the first record came out and was a big hit all around the world and gave us a really good starting point. We thought maybe we could do it for a couple of years—and then it turned into 10 years.

We did have a rest after a while but by 1990, people hadn’t forgotten Procol Harum and wished we were still around doing things. So we got back together again, made a new record in 1990, and were still alright. Years passed and we were still doing it, and then 14 years had passed since we’d been in the studio last, and here we are. But I don’t think you can start something at 20 and think you’ll be doing it for 50 years; I don’t think anyone in music thinks that. It depends on the people and on yourself still being good at what you do. And here we are, 50 years.

Do you think that the band’s approach or its ideology behind making music has changed a lot since it first began? Or is it more or less the same for you—in terms of how you come up with musical ideas?

I think the way I personally come up with an idea is the same as it always was: to play the piano and see what comes out from the ends of the fingertips, through the mind. With this one, we approached it differently because Procol Harum—as it stands today, as we made the record—we’ve been playing live for 10 years, but we’ve not actually been in the studio during that time.

Once we decided that we’d make this new record, we thought, right—we’ll need some new songs. This time I thought I would get some of the others involved in that process. So I got Josh Phillips, the organ player, Jeff Whitehorn on the guitar—and we got together and had a go at things. It worked out fine; if one of us had a start of an idea, we would expand it nicely—so the combination of involving others in the band to this extent was a great success.

How did you find working with Pete Brown, and how did that happen? I know in the past you had worked with Keith Reed on lyrics.

Yes, well Keith must’ve come to a crossroads and made a turn, while we carried straight on. Pete Brown I’ve known as a colleague since the days when he wrote lyrics for an English band called Cream. They’d always done very interesting words, and of course I’d bumped into Pete from time to time; I’d seen him at Jack Bruce’s funeral in 2014. During the course of this, we’d talked about the future and he’d said that he would be very interested in doing a set with Procol and having a go at an album’s worth of songs. When we were doing the writing process, Pete’s name came up a couple of times and so he joined in; he got to see the way we worked.

He got to see the way I work, because I’ve got to sing on the top of all these ideas as well, and I’ve got to have words to sing. So for the singer, they have to be ideas you’re happy singing—not happy/smiling necessarily, but comfortable. You don’t want to sing about something you don’t agree with, or some emotion that’s never been part of you, like anger or rage for instance in my case. Pete could also adapt; if I wasn’t comfortable singing a line, he would put it in the third person. So instead of me singing about me, which I very rarely do, I’d put it in the third person and be more of an objective viewer.

On Novum and on recent recordings, and personally having seen you perform live recently in New York, your voice is so strong. A lot of longtime singers end up losing their voices after years of use, but your voice seems to have maintained that same vigor it’s always had. Do you think it’s because you take better care of your voice, or is it just fate or luck?

I think that it’s something special inside my throat. I’ve never looked down a throat myself, but there are two bits that can bang together, a bit of an anatomical thing. With me though, they don’t bang together, so my voice doesn’t get worn out or sore if I sing for a long time. It also gives me a certain sort of sound I think. As long as you sing the song with a bit of feeling and put yourself into it, the emotional element will be there. Of course as long as the chops are there too, and the enthusiasm, everything will be alright.

Novum is such a great album and it serves as an entire listening experience, kind of like the good old days, when people didn’t just listen to singles, because the whole records were so important to hear from start to finish. Do you think that was part of your idea on this record too? Where you wanted to make an entire listening experience?

I’m a bit old-fashioned and I think the people I work with are as well. We do still think of an album as being a whole entity. It would be lovely if people could put Novum on at the start and play it through all the way—and it would be even better if it was loud coming out of the speakers or even through proper headphones! We were brought up like that, 50 years of making LPs; it’s very hard to get that out of your system, but I also think it’s a good way to do things.

A great deal of the material on this record has very attractive qualities of being present and personal heroism about it. “Last Chance Motel” touches on that a bit—like a triumphant insistence upon continuing.

I think, if you sing or play something or make a record, you have to put all of yourself into it. One of the important things about Novum is that when we approached it, together with our lovely producer Dennis Weinreich, we would record the songs in the studio all playing everything at once, live. That gives it a kind of togetherness—and once we had takes, there wasn’t really much more to do.

We didn’t want to add lots more because the tracks didn’t need it. Overdubs, where you record something and put something on it and that on it and so forth, and change things—here on Novum we didn’t go down that avenue because there was absolutely enough there. We were happy—and that was what you call making a success of it, as far as we’re concerned—to get that kind of thing down on tape or vinyl or whatever it ends up on.

Much of Procol Harum’s music has participated in a musical dialogue with the genre of classical music; “A Whiter Shade of Pale” has its Bach vibe, and here on Novum, “Sunday Morning” references Pachelbel’s Canon. Was this a conscious decision for you, even when you first started the group in the sixties, to involve classical music in your composing?

Yes, well you play in a band when you’re younger, and you start with doing covers mostly, and then move on to original songs. While you’re growing up—basically from the time your ears work—you’re being influenced by music and it does stay in your head. One day I thought I would be a songwriter and write my own songs.

All of your influences come out along with your originality of course—classical music being one of mine, Ray Charles being another. Everything you’ve heard and liked comes into your mind and comes back out mixed up with something different into a new piece. Pachelbel’s Canon—I told Josh and the others while writing that I had this idea, so I started off with those chords from the canon. When we recorded it, Josh played the line underneath.

So it’s not just a reference to the canon, it is an actual part of the canon. But it was a good take so I couldn’t throw it away. To me, it would draw people in, they might think, “Oh, I know this, it’s familiar in some way.” They’ll realize they’re listening to a Procol Harum song, not Pachelbel’s Canon. It’s all part of writing things. It’s a bizarre sort of Procol Harum-y commercialism I think.

Speaking of influences, there were some jazzy pop-rock vibes going on here too: the fantastic album opener “I Told on You,” reminded me a bit of Boz Scaggs’ 1970s work, his Silk Degrees (1976) record. “Image of the Beast” had a touch of Steely Dan’s “Pretzel Logic” (1974). Were you influenced by that 1970s American studio-produced sound?

With Novum we collaborated on the writing and playing, so there is a little bit of that in. I hope the others didn’t copy anybody! “Image of the Beast” does sound a bit jazzy. Usually you can tell a Procol Harum track from the voice, but I disguise myself a bit on a couple of these tracks. Being a singer is sometimes a bit like being an actor, you have to act a part. If you yourself haven’t thought or done what’s in the song, you’d have to put yourself into that character.

Speaking of theatre, “Don’t Get Caught” is such a playful song—it reminded me of Polonius’ advice monologue from Hamlet, when he’s explaining how to be in the world. This song though, had a nursery rhyme vibe along with a simultaneous awareness of the adult world’s occasional hypocrisy.

You’re not meant to do it, but if you do, don’t get caught! I do like that track, it is a bit different. How it came about—musically the background never really changes and the chords are simple, but the vocal line rides up above that. It’s an interesting part to sing. I’m not experimenting anymore. When we do go out on tour, onstage with these songs, we don’t perform them the same way as in the studio. They’re better than that.

“Sunday Morning” is a standout number on Novum—lyrically a bit Springsteen-esque, making the working life into a holy life. Like the yearning to feel free from the constraints of time, which vocally you express so beautifully.

Pure acting. The opening lines “When I leave work on Friday” express the attitude of someone who works all week, and then when Friday night comes around, he just wants to have a really good time. So much so that he hasn’t really got time to go to church on Sunday. But I don’t work on Fridays; I’m not a blue-collar worker or someone who goes into the office five days a week. As an actor though, I have to sing it as if it were true. Luckily it’s not always as literal as that. There is something about singing the words “Sunday Morning” though. I can’t say those words anymore without bursting into song.

In music history that phrase comes up a lot, like Kris Kristofferson with “Sunday Morning Coming Down” and the Velvet Underground’s song “Sunday Morning”—

Have they got one called “Sunday Morning”? Oh, no. Well, nothing’s original of course, especially song titles. But you couldn’t call this track much else but ‘Sunday Morning” I suppose.

Though you’re not a nine-to-five guy, do you ever feel constrained by time in a similar way? How do you feel about your own relationship to time and work?

There isn’t enough time around; I’d say there’s a lack of it. I kind of prefer to drift around a bit all day when I can, I’m not a great multi-tasker. I go through times when I walk from room to room not quite sure what I’m looking for but I’m engaged in the experience.

That way of behaving almost seems more instinctual—rather than going by this rigid schedule.

Rushing about doing everything doesn’t seem very natural to me. I’m sure stone-age man didn’t do that. He was too busy inventing fire, whacking two rocks together all day.

“Somewhen,” the last track off the record, has a beautiful hymnal quality to it and is much simpler in production than the other songs.

Just me and the piano.

That contrast was a nice way to close the album. The song has a sacred musical sound—do you think that you have an ongoing musical dialogue with religious music? Are you influenced by church music?

I think the influence is there because when I was little I was a professional page boy. What that is—well imagine there’s a woman getting married, she’s got this long white dress with a train behind it. There used to be a little girl dressed very prettily holding one side of that train and a little boy dressed in a white satin shirt and black trousers on the other. And that was me, on the left.

I’ve grown out of the trousers since then. I grew up with the hymns because we had them in church and in school, at least when I was there—and the music did come in. When you think of J.S. Bach, he wrote one little tune for every Sunday morning—there’s “Sunday Morning” come up again. Bach really did though, he wrote them to be sung by the choir and played by the organist. Nowadays every one of them’s a classic piece.

Generally, in music there’s a spirituality of things that has to be there, even if it’s not overt. We’re trying to pave our way to Nirvana, really. You don’t want to go downstairs and get burnt, or end up absolutely nowhere. Much better to head to the pearly gates.

When you’re composing, do you ever think of images and visuals? Does film inspire you in any way? Some of the past Procol records like Grand Hotel are sweepingly cinematic and visually evocative.

Yes, it is about creating some sort of picture, musically. We don’t look at it that closely; it’s more about creating an atmosphere. If you can create an atmosphere, it can translate itself into something visual.

In other words, if you can hear something, you can imagine a scene, be it a dark forest or a long green meadow with a sunset in the background. Without being over-specific, that’s called atmosphere, which I think comes into it in the writing, in the creative process. But it’s quite deep down in there. I don’t ever think, “Oh, I’ll write one that depicts a fabulously old-fashioned brilliant hotel.” You just get a picture of an old hotel that I’ve probably been in, where you walk in and there’s a little orchestra playing in the foyer or a pianist in the background and some gypsy violinist walking around the tables—and suddenly you’re there.

Do you think of Procol Harum’s music as being particularly British, or as celebrating British life? Kind of like the Kinks’ music does?

No, I don’t. The Kinks were absolutely brilliant at it; the Small Faces were as well. Very good words and very British about it, but not in a comedic way. There’s nothing very comedic about the Kinks or Ray Davies, but the music has a very British outlook. I’ve always thought that Procol Harum’s music was more European in some way—not just modern European, but covering-the-last-300-hundred-years European.

Of course you can’t cover America on that kind of time span because America hasn’t been around all that long, and of course American music hasn’t either. Pachelbel’s Canon was late 1600s I think; all that musical history and melody history goes back a long, long way. Church music specifically.

Procol Harum’s definitely not an American band, and we’ve never tried to be like one because they’re so good, you know. But we’re not trying to be like anybody else, not anymore—I used to want to be Ray Charles, that’s good American music—and so are The Eagles and The Beach Boys. All that’s very American, you wouldn’t hear that music from a British band.

Have you ever worked with those American bands or toured with them?

Procol Harum was actually supported by the Eagles on tour in 1972. They were very good, their first record had just come out, and “Take it Easy” was then a hit for them, which was very nice. That was at the start of their career really. I still see Joe Walsh now and again; he invited me up when they played at the O2 in London a couple of years ago, I went and saw them. They were excellent, but the life that the Eagles leads is very different from the life that Procol Harum leads.

While you were making Novum and then finalizing it, what other records were you listening to? Do you think that anything you listened to influenced the sound of the record?

The simple answer to that I’m afraid is: no. Nothing. When you’re actually in the process of making an album, you don’t listen to anything else whatsoever. You work on and record something, and then the end of the day comes.

The next day the first thing you want to hear is what you did last night; then you might do it again, or might not. Then you move on to the next one and the process continues; you never listen to anything else. You’ll take away a rough mix of something and that’s what you’ll put on in the car. Everything else will sound just alien; it gets very, very self-centered for a while there. There isn’t much that pricks one’s ears up these days I’m afraid. You have to really delve in to find things that are good.

Did you realize anything about yourself while making the record? Did you have any revelations about your life?

Just—I’m glad I’m around. Mortality comes into life now and again [laughs]—well of course it does—I had a fall on stage a few weeks ago and got a broken hand; it’s mending now. But you’re suddenly quite grateful for being here at all—so you’ve got to live for today as well.

What’s up next for you project-wise? I know Procol Harum has a European tour coming up.

We’re going out in Britain first starting in May and then I’ve got various other things happening; I’m going off to sing in Estonia soon. Then we’re all around Europe starting in September, and we’re waiting for some American dates to come along. We might have something there in February; things work a long ways in advance these days with rock music and touring.