Joel Paterson knows the guitar. He relates to its history, believes in its progression of instrumental prowess, its evolution of sonics over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and he creates his own version to introduce a new modern guitar dialogue for other players to commune with and respond to. Studying the antics and musical choices of guitarists from long ago and recent pasts, players ranging from Blues pioneer Robert Johnson to The Clash’s Mick Jones, Paterson maintains an intimate relationship with the instrument—which can only result in topnotch musical output.

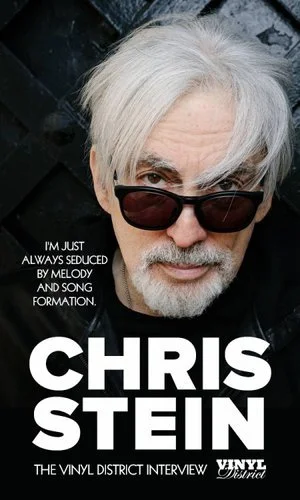

Over the course of the memoir that covers Stein’s youth and formative years as an artist up until present day, Stein confronts his own life and artistic legacy with a down-to-earth grace and enlightened candor rarely found in a rock autobiography. And by reliving Stein’s and his group’s past along with him, one is left with the knowing feeling that they most definitely did succeed insofar as leaving a permanent cultural and artistic imprint on the world of music.

How does one write a biography of one of the most definitive, elusive, and ever-changing artists in the history of popular music? Perhaps, by abandoning any intention to include any straightforward, linear qualities that a so-called traditional biography might promise.

Bob Dylan contains multitudes, as articulated in his song riffing on Walt Whitman’s concept, on the 2020 album release Rough and Rowdy Ways. And this is evident once again in Dylan’s new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song.

Throughout his complex and regenerative career, all of his different sides, and the characters within him, are tangible. The best writer is often the most empathic, able to inhabit the world and emotional memory of a character who exists universes away or who does not exist in real life at all. He is a changer, a shifter, malleable, and belonging to the world and all of its individuals and their probable and potential selves, beyond his own assigned self.

Then there is Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone, the publication created in 1967 that gave voice to the youth culture, the hippies, and leant them a stake in the Real World. The magazine invented a pre-internet meeting place where rock ‘n’ roll was given the reverence that it deserved, in which once could connect with likeminded music-mad people. Last month Jann published his memoir Like a Rolling Stone, a weighty tome surpassing five hundred pages. It came somewhat on the heels of the well-received and somewhat character-damning Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan, Wenner’s biographer who he eventually parted ways with mid-project. Like a Rolling Stone is Wenner by Wenner, period.

Lovelorn music man Lester the Nightfly, a major player on Donald Fagen’s 1982 solo album The Nightfly, is a character with a complex identity. At first contemplation, he’s a jazz DJ on the nightshift during the golden, Camelot era of American life in the early ’60s, fielding calls from a cornucopia of after-hour nutsos while holding steady with his jazz heroes whose music he showcases across the night and out into the airwaves.

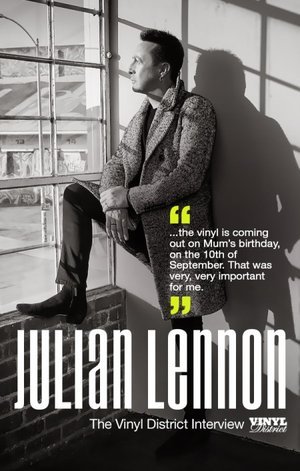

The choice of album title, Jude, an allusion to Paul McCartney’s Beatles song written to Julian during a difficult time following his parents’ split—and his choice of album cover photo featuring his young self—suggests a kind of full circle of the individual. As in to know, understand, and feel close to one’s childhood self is to accept one’s truest, most uncompromised self.

The story of Creedence Clearwater Revival in the 1960s and ’70s, of John Fogerty’s drive and determination to become a true artist and performer, songwriter, and lush compositional mythmaker, is a fascinating one. CCR was a band who in part defined the sound of the late 1960s in American rock, who had its share of issues and squabbles, who was ultimately run by John and the vision he had for himself and his music which led to immense commercial success and a fair share of legal battles and artistic frustration in the decades following.

Possessing a penchant for self-examination and introspection, Beckley favors the navigational terrain of the ever-elusive human heart—and its frenemy the mind—and the moments when they do and do not work together when carving out compositions.

Hearty Har, whose creative nucleus consists of Shane and Tyler Fogerty, possesses a plethora of creative influences. And while the duo did cut some of their performative teeth backing up their dad—rock legend John Fogerty, the co-founder of Creedence Clearwater Revival—during recent live tours, Hearty Har’s true gift for musical expression appears to lie in recording studio prowess, or so the band’s debut studio album Radio Astro, released last month, would suggest.

Much like the families and groups from which it was bred and sprung, The Allman Betts Band has consistently thrived as a live performance act. But just last year they proved their studio mettle by releasing a debut album Down to the River, and in late August of this year—and what a strange and volatile year it has been for the universe—they released Bless Your Heart, a versatile, expansive, and guitar-driven record that serves as a testament to the band’s studio abilities.

The son of rock legend Gerry Beckley of America, Matt was a part of the professional world of popular music since birth. He grew up on the floors of recording studios in Los Angeles in awe of his father’s artistic prowess and the magic of making music, while at the same time understanding the realities of the recording artist’s vocation and its tangibility. While some young people exposed to such a situation might take it for granted or rebel against it, Matt possessed the intelligence and inherent artistic impulse to desire knowledge and experience, knowing he held an innate ability and interest to add something new to the ongoing legacy of recorded music.

Smack in the middle of an era full of complications—and amidst a year of fear and confusion—singer-songwriter Sasha Dobson has released her four-song EP “Simple Things” that reminds all of us to divert our attention toward what truly matters.

“Seems impossible to tell seasons apart, or know exactly which way the weather’s going to go,” states singer-songwriter Marcus Eaton in “Closer,” the third moodily introspective track on his EP “Invisible Lines,” released last month on vinyl. New and timely in its themes of isolation, sociological questioning, and nature awareness, Eaton’s EP stands as a semi-unintentional testament to the wild, sad, and unpredictable times we are currently living through.

When it comes to approach of identity-definition, there are two kinds of artists.

The first kind develops his/her craft and his idiom as far as they can go, and then, once sensing that the craft and idiom have within themselves some kind of success-potential for communication of ideas and sentiments, settles upon them. The artist decides to perfect his/her selected approach - and perform it and publish it - again and again and again. And it works well. Audiences who dig it do dig it and don’t ask questions.

The second kind possesses and revels in his/her craft and his idiom as parts of him/herself, and then, once sensing their abilities and limitations in terms of potential for artistic achievement, rejects them. The artist decides that s/he will reinvent the selected craft - and dress it in different fabrics and colors and styles - again and again and again. And it works well. Audiences who dig it do dig it, mostly, and ask an ongoing plethora of ever-changing questions as they bear witness to the eternal evolution of the artist’s craft.

“I wish I had a heart like ice,” Donald Fagen—or rather his character, uber-hip yet lovelorn jazz DJ Lester—yearns in “The Nightfly.” The track is a high point on an autobiography-infused nostalgiAlbum of high points. The Nightfly, Fagen’s debut solo recording—which also featured classics “I.G.Y.” and “New Frontier”—was nominated for seven Grammy awards and released in 1982.

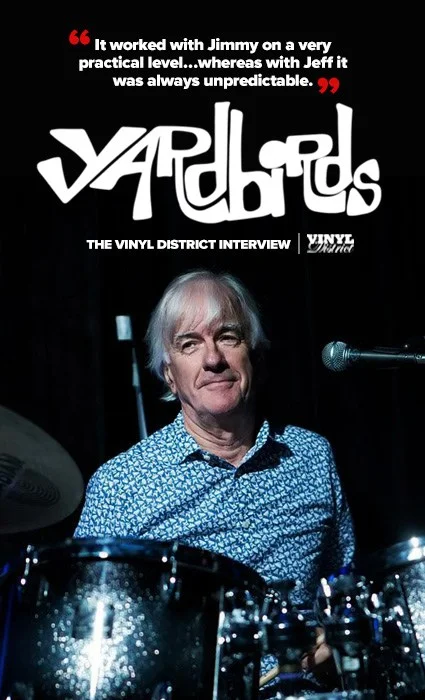

There are two schools of thought when it comes to band legacies. The first being—once the original lineup is disbanded, the band is dead forever, its name included. The second being—as long as a founding member or two remain involved, as long as a spark of the band’s core identity somehow remains, the band can go on living and using its name. The Yardbirds are of the second school, and for the past few decades, drummer-composer Jim McCarty has led the blues-rock group that he co-founded in a way that maintains its awe-worthy history and simultaneously insists upon a perpetual newness. The same kind of newness that accompanied the Yardbirds’ nightly rave-ups during their early ‘60s Crawdaddy Club residency, once the Rolling Stones had outgrown the role.

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, All Things Must Pass, and Exile on Main St.—three rock and roll albums with several captivating commonalities. All were recorded and released in the early 1970s. All are now widely regarded as some of the most remarkable albums ever made in the history of popular music. All were included on Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums of All Time” list, too. And all featured singer-keyboardist extraordinaire Bobby Whitlock.

Fifty years into a legendary career, most bands are content to rest on their hits, releasing bland blues covers albums or bored-yet-pleasant regurgitations of their earliest work. Procol Harum is not “most bands.”On the 50th anniversary of their debut album, the English prog rock icons continue to remain a singular force in modern rock music, embracing the new-song, best-song philosophy on their first album in 14 years, Novum, out on Friday, April 21, via Eagle Records.

Before the Steve Miller Band, there was the Steve Miller Blues Band. Before the Joker, before the Space Cowboy, before Maurice, there was Steve – guitarist extraordinaire, young, beautiful, and insanely talented, with an intense affinity for and knowledge of American Blues and Roots music. This Steve, in conjunction with Jazz at Lincoln Center, has been responsible for shining a bright light on the important historical and artistic roles that Blues guitar has played in American history - and, stemming from that, the role that Blues guitar has played in Steve Miller’s artistic journey. Some musicians seem to move further and further away from their creative roots and influences as they become more and more grounded in their lasting legacy, a legacy that propels itself into the future. But Steve is smarter than them; he always was.